I am going to be honest for a moment, which, given my track record, is almost impossible. When I sat down to write this article, I had absolutely no idea about what I was going to write. Think about it. The NFL is in the midst of its three-week offseason. The NBA’s jam-packed schedule has turned games into a display of S&M — shabby and mistake-prone. Speaking of which, it might be a good idea to add the Bobcats and Hornets along with the Raptors to the list of extinct species. Of course, I could write about soccer, my de facto area of expertise, but then I would run the risk of alienating the three law-abiding readers I have left.

I am going to be honest for a moment, which, given my track record, is almost impossible. When I sat down to write this article, I had absolutely no idea about what I was going to write. Think about it. The NFL is in the midst of its three-week offseason. The NBA’s jam-packed schedule has turned games into a display of S&M — shabby and mistake-prone. Speaking of which, it might be a good idea to add the Bobcats and Hornets along with the Raptors to the list of extinct species. Of course, I could write about soccer, my de facto area of expertise, but then I would run the risk of alienating the three law-abiding readers I have left.

Then, it hit me: A picture frame fell off my shelf. Instead of wasting valuable column space dancing around the fact that I have writer’s block, I could always write about you, the often-underappreciated fan (and the other two reading this, of course).

Shortly after the Super Bowl ended, there was a great deal made about Patriots tight end Rob Gronkowski dancing shirtless after his team lost the game. Normally dancing shirtless doesn’t have the disgust-factor of, say, a middle-aged sportswriter gyrating sans button-down in the middle of a crowded room. The response stood in direct contrast to that of Wes Welker, whose dropped pass was repeatedly blamed for the defeat, the receiver beside himself afterwards. The philosopher in me — the one that usually wonders why flammable and inflammable mean the same thing — naturally wondered: Do the fans take winning and losing harder than the players do?

I grew up in a household where if I even considered the thought of rooting for teams other than the Lakers, Dodgers, or UCLA, I would be cut out of the inheritance. With the exception of a couple of notable title runs during my lifetime, cheering for that troika naturally turned me into the bitter, self-hating apologist that I am. I could go on, but I’d just be copying and pasting from my college entrance essay. Though I was familiar with cheering for losing teams that intermittently paraded out every Billy Ashley and Anthony Peeler known to man, I tried not to get as caught up emotionally in my sports as I do watching “Downton Abbey”, for instance. (Those dowagers sure pull on the heartstrings.)

A lot of fans throughout sports history do not follow suit, however. Understandably, rooting for certain sports teams are rooted in an area’s DNA, for better or worse. Chicagoans have stuck by their Lovable Losers. Clevelanders tell anyone who will listen that this year will be the year, though the Kardiac Kids have long since passed, and any other sports team in the city is bound to give a diehard an infarction. It’s not uncommon to see a Milwaukeean cry into their hops regardless of the color of the leaves outside. But what about the athletes themselves?

Gronkowski’s Flashdance was by no means the first time an athlete was seen to be so buoyant after a big game loss. Sure, Kool & the Gang have implored people to celebrate good times, but I’m assuming those lyrics were by no means inclusive. However, odds are that one will fine a large swath of fans that are more inconsolable than the players themselves after a big game loss and vastly more excited after a major triumph. The next time athletes stand shoulder-to-shoulder with fans after a loss (or win) turning over cars and smashing store windows might be the first (though most of the rec-league softball teams I played on would put a dent in that theory). It is said that the truly dedicated sportsmen wear their heart on their sleeve. If that truly is the case, someone better consult a team of cardiologists, because my college-level anatomy charts were all wrong.

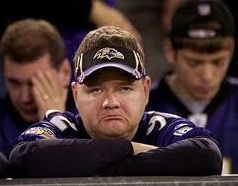

The fans don’t just wear their heart on their sleeves; they also wear a variety of condiments and liquids of a caloric nature on them. (Hygiene and sports fandom are often inversely related in my experience.) Multiply the disappointment for the typical sports fan following a loss and you will approximate what the defeat feels like. Some go into a depressive funk that would make Grunge music look like the Fifth Dimension. Others take their anger out on various freestanding household items, or simply demonstrate on the local news to their city’s baseball team the way a bat was meant to be swung, or to the football team how to rush through a wall of blocking officers. A win means bragging rights, everything is right with the world. That is, until the realization comes that the playoff share will not be getting deposited in one’s bank account anytime soon.

But for the athlete? Sure, there are plenty examples of the college athletes crying on the end of the bench when March Madness becomes March sadness. Or, the stories of Olympians who realize that they may have missed out on the window for glory. There are the Ron Artests (or whatever you want to call him these days) who are so happy when they win, they don’t even bother to remove their jerseys when they go on an imbibing run, as the Lakers’ forward did back in 2010. But, for a lot of the heroes of the cloth — I believe it’s breathable mesh — losing on the big stage is like a bad day at work: You get paid, you perform, things don’t go right, but you move on. How many folks do you know at the job who descend into a state of despair if a series of documents didn’t collate properly? I’ve seen civil servants deliver mail to the wrong address, it’s not like they go postal… Uh, bad example.

In Los Angeles, there are a couple of well-known models of athlete apathy involving Cedric Ceballos and Nick Van Exel. For many players, the rigors of an 82-game season can be taxing. In 1996, Ceballos apparently felt the need to take the family and jet skis to Lake Havasu ostensibly to get his spring break on, maybe feeling worn-out despite the fact the season was only 8 games old. He later blamed mechanical failure — either brain or jet ski-induced — as to the reason why he ended up missing a game in Seattle soon after.

In 1998, the Lakers were one game away from being swept out of the playoffs by Utah and, as the team huddled after practice, Nicky V. infamously led a cheer “1-2-3, Cancun.” Such an act symbolizes the reaction of a lot of athletes. A small percentage of pro athletes ever get the chance to play for a title. Sure, most would love to win it all, but they also know that an early exit isn’t so bad, even if that cheer was a prelude to Van Exel’s exit from LA to presumably the polar opposite of Cancun, Denver. But, look, fans are unabashed passionate observers of sports. The word “fan” comes from “fanatic.” Why else would someone go take off their shirt, paint up their body and wear a block of foam cheese on their heads? You wouldn’t expect such behavior from Aaron Rodgers, would you?

Just remember that the next time your team suffers a defeat, that it is truly not the end of the world. The sun will still rise, and things will improve. Just be happy no one’s booing you if the stapler gets misplaced. Now that would be pressure. Sometimes, things on the job just don’t work out.

That reminds me, I don’t think I’ve come up with anything to write about yet.