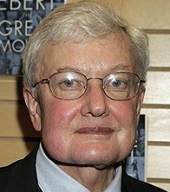

Roger Ebert died Thursday at the age of 70. Ebert was not only one of the greatest film critics of our time, but also a fantastic writer. The man won a Pulitzer Prize and entertained us with his great movie reviews both in writing and on TV.

Roger Ebert died Thursday at the age of 70. Ebert was not only one of the greatest film critics of our time, but also a fantastic writer. The man won a Pulitzer Prize and entertained us with his great movie reviews both in writing and on TV.

As I have gotten more and more into movies over time, I started comparing my reviews of a movie to those of the critics. More often than not, my thoughts seemed to agree most with Ebert’s. The man had an excellent way of expressing his thoughts and, despite not being overly critical, was not afraid to say when he disliked a movie.

In honor of Ebert, we decided to share portions of his reviews of some of the most notable sports movies.

A film like “Hoop Dreams” is what the movies are for. It takes us, shakes us, and make us think in new ways about the world around us. It gives us the impression of having touched life itself.

[…]

Many filmgoers are reluctant to see documentaries, for reasons I’ve never understood; the good ones are frequently more absorbing and entertaining than fiction. “Hoop Dreams,” however, is not only a documentary. It is also poetry and prose, muckraking and expose, journalism and polemic. It is one of the great moviegoing experiences of my lifetime.

The climax of the movie will come as no great surprise to anyone who has seen other sports movies. “Hoosiers” works a magic, however, in getting us to really care about the fate of the team and the people depending on it. In the way it combines sports with human nature, it reminded me of another wonderful Indiana sports movie, “Breaking Away.” It’s a movie that is all heart.

As “Field of Dreams” developed this fantasy, I found myself being willingly drawn into it. Movies are often so timid these days, so afraid to take flights of the imagination, that there is something grand and brave about a movie where a voice tells a farmer to build a baseball diamond so that Shoeless Joe Jackson can materialize out of the cornfield and hit a few fly balls. This is the kind of movie Frank Capra might have directed, and James Stewart might have starred in — a movie about dreams.

This man we see is not, I think, supposed to be any more subtle than he seems. He does not have additional “qualities” to share with us. He is an engine driven by his own rage. The equation between his prizefighting and his sexuality is inescapable, and we see the trap he’s in: LaMotta is the victim of base needs and instincts that, in his case, are not accompanied by the insights and maturity necessary for him to cope with them. The raging bull. The poor sap.

This is strange. I have no interest in running and am not a partisan in the British class system. Then why should I have been so deeply moved by CHARIOTS OF FIRE, a British film that has running and class as its subjects? I’ve toyed with that question since I first saw this remarkable film in May 1981 at the Cannes Film Festival, and I believe the answer is rather simple: Like many great films, CHARIOTS OF FIRE takes its nominal subjects as occasions for much larger statements about human nature.

[…]

CHARIOTS OF FIRE is one of the best films of recent years, a memory of a time when men still believed you could win a race if only you wanted to badly enough.

What makes the movie extraordinary is that it doesn’t try to surprise us with an original plot, with twists and complications; it wants to involve us on an elemental, a sometimes savage, level. It’s about heroism and realizing your potential, about taking your best shot and sticking by your girl. It sounds not only clichéd but corny — and yet it’s not, not a bit, because it really does work on those levels. It involves us emotionally, it makes us commit ourselves: We find, maybe to our surprise after remaining detached during so many movies, that this time we care.

I was at a reading where he made audience members cry with his description of the death of Secretariat, and I saw people crying after “Seabiscuit,” too. It’s yet more evidence for my theory that people more readily cry at movies not because of sadness, but because of goodness and courage.

Underdog movies are a durable genre and never go out of style. They’re fairly predictable, in the sense that few movie underdogs ever lose in the big last scene. The notion is enormously appealing, however, because everyone can identify in one way or another.

This opening evocation is matched by the closing shots of “He Got Game,” in which Lee goes beyond reality to find the perfect way to end his film: His final image is simple and very daring, and goes beyond words or plot to summarize the heart of the story. Seeing his films, I am saddened by how many filmmakers allow themselves to fall into the lazy rhythms of TV, where groups of people exchange dialogue. Movies are not just conversations on film; they can give us images that transform.

“Space Jam” is a happy marriage of good ideas–three films for the price of one, giving us a comic treatment of the career adventures of Michael Jordan, crossed with a Looney Tunes cartoon and some showbiz warfare.

Oddly enough, despite all these undertones, “Friday Night Lights” does also work like a traditional sports movie, and there’s enormous tension and excitement at the end, when everything comes down to the last play in the state finals. The movie demonstrates the power of sports to involve us; we don’t live in Odessa and are watching a game played 16 years ago, and we get all wound up.

“Remember the Titans” is a parable about racial harmony, yoked to the formula of a sports movie. Victories over racism and victories over opposing teams alternate so quickly that sometimes we’re not sure if we’re cheering for tolerance or touchdowns. Real life is never this simple, but then that’s what the movies are for–to improve on life, and give it the illusion of form and purpose.

These days too many children’s movies are infected by the virus of Winning, as if kids are nothing more than underage pro athletes, and the values of Vince Lombardi prevail: It’s not how you play the game, but whether you win or lose. This is a movie that breaks with that tradition, that allows its kids to be kids, that shows them in the insular world of imagination and dreaming that children create entirely apart from adult domains and values.

Michael Ritchie’s “The Bad News Bears” is intended as a comedy, and there are, to be sure, a lot of laughs in it. But it’s something more, something deeper, than what it first appears to be. It’s an unblinking, scathing look at competition in American society – and because the competitors in this case are Little Leaguers, the movie has passages that are very disturbing.

Oliver Stone’s “Any Given Sunday” is a smart sports movie almost swamped by production overkill. The movie alternates sharp and observant dramatic scenes with MTV-style montages and incomprehensible sports footage. It’s a miracle the underlying story survives, but it does.

The movie contains a certain amount of basketball, but for once here’s a sports movie where everything doesn’t depend on who wins the big game. It’s how they win it.

Maybe one of the movie’s problems is that the central characters are never really involved in the same action. Murray’s off on his own, fighting gophers. Dangerfield arrives, devastates, exits. Knight is busy impressing the caddies, making vague promises about scholarships, and launching boats. If they were somehow all drawn together into the same story, maybe we’d be carried along more confidently. But Caddyshack feels more like a movie that was written rather loosely, so that when shooting began there was freedom_too much freedom_for it to wander off in all directions in search of comic inspiration.

`The Cutting Edge” is a marriage of two durable Hollywood genres: It’s an Underdog in Training sports film, crossed with that most beloved of all romantic formulas, the Incompatibles in Love.

There is essentially not an original moment in the entire film, and yet it’s skillfully made and well-acted.

Come on, give us a break. The last shot is cheap and phony. Either he hits the homer and then dies, or his bleeding was just a false alarm. If the bleeding was a false alarm, then everything else in the movie was false, too. But I guess that doesn’t matter, because THE NATURAL gives every sign of a story that’s been seriously meddled with.

That should have been obvious, but the filmmakers didn’t care to extend themselves beyond the obvious commercial possibilities of their first dim idea. As for Shaquille O’Neal, given his own three wishes the next time, he should go for a script, a director and an interesting character.

If the writing had been smarter – if it had been about a plausible baseball team, instead of about a group of sitcom clowns – maybe something would have worked.

There’s one bright spot: On the basis of this dismal attempt, the team will probably not be back next season.

Note: Ebert did not see the first film. He was also wrong about there not being a third movie haha.

Ebert also had an epic takedown of former Chicago Sun-Times columnist Jay Mariotti that is a must read.

If you’re looking for more Ebert reading, we suggest this Esquire feature on him and his battle with cancer.

An assist to Sporting News, USA Today